When Sally Harrison starts work on a painting, she is never sure where her hand will take her.

“After 27 years I’m finally getting the hang of letting my hand go where it will on the canvas,” she said.

Sally meanders here or there on her artwork like a river.

Her life, in many ways, has mirrored the rhythm of a river, filled with plenty of obstacles, twists and turns.

Whether it be the Murray, the Shoalhaven or indeed the Bremer, Sally has spent her life on one side of a river or another.

A tough beginning

It was in The Land of The Jardwa (The Wimmera, Victoria) where Sally’s story began.

Her mother, Jessie, was just 14 when she was raped by a 33-year-old white man at Swan Hill.

Sally was born on Australia Day 1949.

Sally’s mother was dumped in a tent on the banks of the Murray River in NSW where she struggled to care for four-month- old Sally.

“I was very sick with the flu. She was on her own with no money to buy medication for me, and didn’t know how to care for me” Sally said.

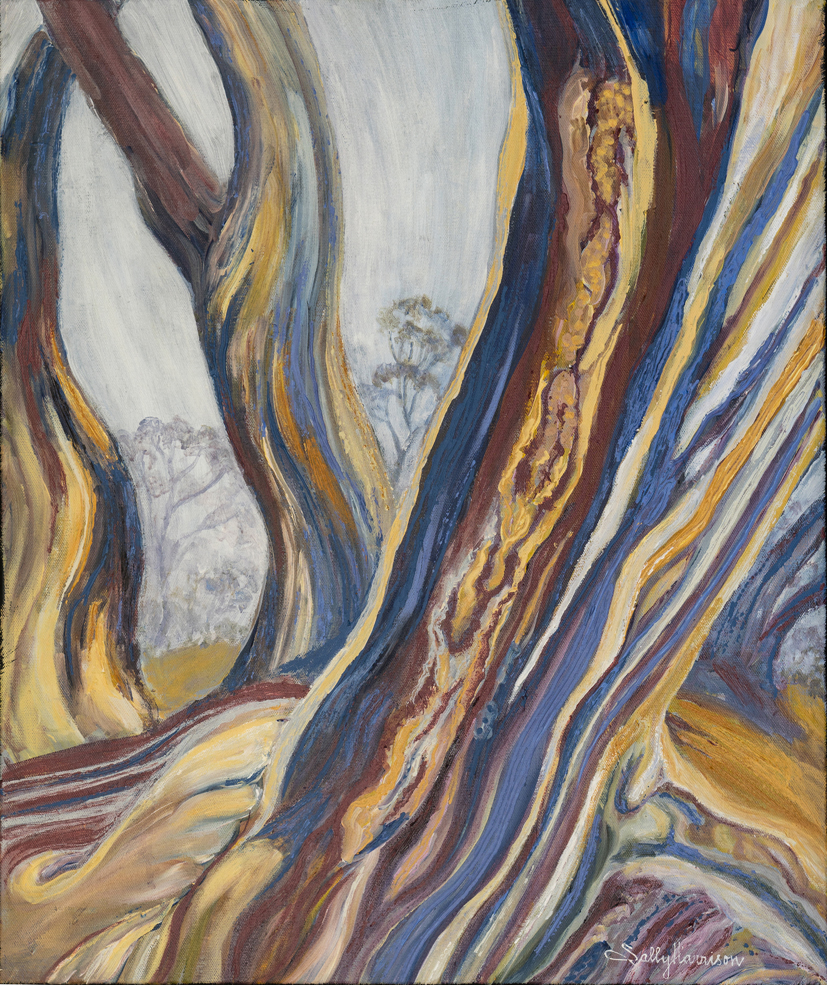

Primordial Snow Gums (Lapislazuli)

“The superintendent of police of Wagga argued with Swan Hill police about whose responsibility we were, given Jessie was an aboriginal from Victoria but living on the New South Wales side of the river.

“After exchanging many letters, it was agreed the only way we could be legally put in care was to charge us under the Fugitive Offenders’ Act as Neglected Children.

“So we were sent to Cummeragunja mission.”

It was the beginning of the end for Sally’s time with her mother.

At first, Jessie was allowed to visit while Matron Petersen cared for Sally in her own home.

However, when Sally was 13 months old, she became a part of Australia’s Stolen Generation when Jessie was sent from one border town to another at Boggabilla, on the border of Goondoowindi in Queensland.

Sally was removed to Bomaderry on the northern side of the Shoalhaven River, south of Sydney.

The Glade of Tranquility 2019

Light and shade in Bomaderry

Bomaderry is where Sally’s character and earliest memory was formed.

“I remember lying in a cot when a burst of sunlight lit up the bare wooden wall on the other side of the empty dormitory,” she said.

“It looked like molten honey as it slid down the wall.

“I watched in fascination as it began to creep across the floor towards me.

“It disappeared, then suddenly it crept up through the bars of my cot, over the covers and touched my arm which felt deliciously warm.

“Then at last it moved right up and kissed me good morning.”

Not all of her early memories are so beautiful and she discovered at a very young age that she would have to look after herself.

While she was still one year old she was forced to toilet train herself in the face of a less than inviting potty.

“I think I was about 16 months old when I was desperate to go to the toilet in the middle of the night,” she said.

“We had big flat jam tins with serrated edges for our potties,” she said.

“I was half asleep and I tried to position myself over this tin without cutting my backside but I kept wobbling.

“I made the decision that I was a big girl and could wait till the morning.

“So I hopped back into bed, forgot all about it and fell fast asleep..

“I woke up in the morning dry and clean in bed and I was proud of myself.

“Serrated edged potties were very good for toilet training.”

A broken promise

The missionaries at Bomaderry taught the children that adoption was a great honour and privilege.

So when Sally’s promise of a family arrived, it should have been a time of optimism for the then five year old.

In reality, Sally’s life was turned upside down as the values of honesty, self-discipline, respect and courtesy she learned at Bomaderry were cast aside by her new parents and replaced with lies, sadism, physical and sexual abuse and mental torture.

“My father made my skin crawl and my mother made my blood run cold but I always blamed myself,” Sally said.

“I should have told Sister Kennedy I didn’t like them and didn’t want to leave Bomaderry.

“I felt duty-bound to say yes because it was drummed into our heads every day of our lives that going away to live was a great honour and privilege.

“I was too scared to say no and I’ve paid for it ever since.”

By the age of 12 Sally had attempted suicide three times.

She said her situation was the ‘same old story’ of sexual, mental and physical abuse behind closed doors.

“It’s endemic in this country in working class society,” Sally said.

“It won’t change until people choose to take responsibility for what they choose to think, say and do.”

A promising discovery

Despite her circumstances, Sally found a way.

From the age of eight to the age of 12, she helped her parents clean the Commonwealth Bank until about 8pm.

“I dusted and polished all the counters, tidied all the bank slips, polished the brass hand plates and kick plates on the big double doors and emptied all the bins, and wiped down the phones and ash trays,” she said.

“Then I was allowed to sit in the staff room and wait for my parents to finish at about 9pm.

It was here Sally started to glimpse a world outside the cruel one she was stuck in.

“Reading really excited me,” Sally said.

“I decided to teach myself to read TIME magazine by trying to understand the stories by fitting together all the words I knew.

“I paid close attention to spelling at school and applied what I learnt in the staff room at night.

“By the time I was nine, I was reading National Geographic, The English Women’s Weekly; Australian Women’s Weekly, Reader’s Digest and the Washington Saturday Evening Post, which was my favourite.

Cascading Hibiscus (Booval Street scene)

“It had Norman Rockwell paintings which I loved looking at.”

Although Sally never mentioned her problems at home, the nuns at St Michael’s school knew something was wrong.

Her teachers always wrote on her school report cards ‘Sally can do better.’

“When I was 10, Mother Michael and a younger nun came to our house and spoke to my mother,” Sally said.

“She said something like ‘we think Sally is very talented but she struggles with some subjects. She’s very nervous and anxious and we think that art would be very good for her. We think it will help her to relax and might help her do better with arithmetic’.”

This was how Sally was introduced to the world of art.

Every Saturday, she attended art classes at the nearby high school, where her teacher, Mr Thurgate, had a profound impact on her.

He was a kind and understanding man who taught her to relax and praised her when she painted spontaneously.

“I went for lessons until I was 15 and at the end of each year I received the best artist prize at the technical college award night,” she said.

After Sally finished school she got a job as a legal secretary.

When her boss, Mr Morton, saw her artwork he offered to pay for Sally to attend the East Sydney School of Art.

“I was so excited I could hardly breathe,” Sally said.

“I went home and asked my parents but my mother said ‘you can go back and tell Mr Morton that you can’t go’ and crushed me like a bug. I was so ashamed to throw it back in his face.

“After that I decided to stop painting so she would never ever again bask in the reflected glory of my achievements and claim it was her doing. I didn’t paint for years afterwards.”

Mammae Hill Edgar Springs Pyramid Station, Pilbara WA

Another bend in the river

After suffering years of abuse, Sally started to break down with anxiety and lack of sleep.

It was a long road, but she was finally passed all the requirements and health tests to qualify for enlistment in the Air Force for six years.

“It was great, the best decision I ever made,” she said.

“It got me out of my shell and I met people from all different walks of life, ethnic backgrounds.

“I even started to paint again.

“I was so ignorant of the world. It was like I’d come out from under a cabbage leaf.

“I didn’t understand banter or double entendres, which went straight over my head because I was never allowed any friendships outside of school.

“As a result the airmen, senior NCOs, pilots and war heroes took me under their wing and became surrogate brothers, uncles and fathers to me.

“I got to fly all over the country.”

Sally met her husband who was also serving in the Air Force.

Sadly, it was to be another twisted bend in her river.

“He was basically a good man, but was a hopeless alcoholic,” she said.

“I just walked away with what I could carry.”

A new beginning

When Sally found her feet once more she headed off to Western Australia to work as a cook on a scallop trawler.

“But I couldn’t stand the diesel smell and the rough conditions in the open sea made me violently ill,” Sally said.

“So my friend took over the cooking and I went onto the deck to shuck scallops.

“Standing in scallop guts that came halfway up my calves, the crew pumped sea water over the decks to wash them overboard.

“The gunnels of the boat only reached my knees.

“As I was puking over the side, I saw that the water was alive with white tipped reef sharks feeding on the scallop guts.

“I thought if I wasn’t careful, they could be eating me.”

Sally made it back to land but found herself penniless and alone on the other side of the country.

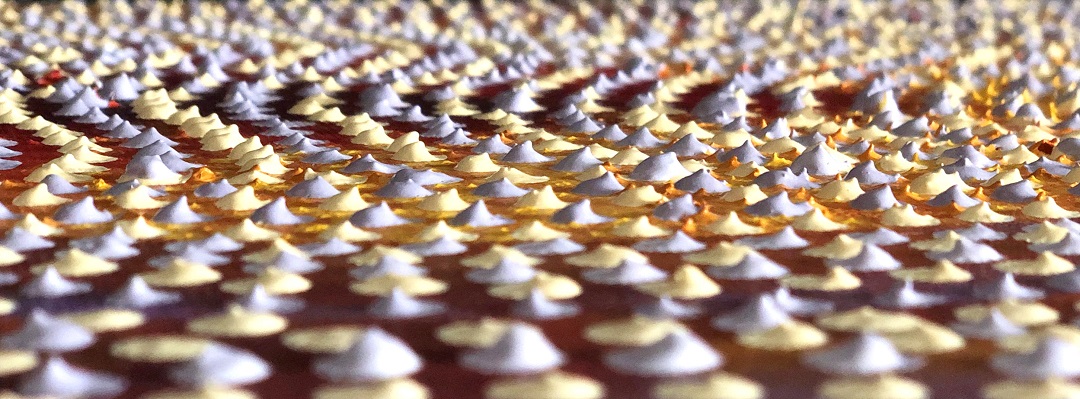

Walking down a street in Carnarvon, Sally saw the local branch of SkillShare was offering an Aboriginal skills course teaching emu egg carving, screen printing and dot painting,” she said.

“But there was no one there to teach me dot painting.

“I was given a book on Western Desert art and told to teach myself to dot and get ideas from the paintings in that book, which was a big no-no, but I didn’t know that until I started to research Aboriginal culture 12 years later.”

That was the first time, in her 40s, that Sally cracked opened the door on her Aboriginal side.

“That’s the first time I knew anything about Aboriginal art and decided to face the issue of my Aboriginality, because it had always been a closed door that I was forbidden to open,” she said.

“The Assimilation Policy expressly banned all contact with aboriginals, my family and my former friends and missionaries at the United Aborigines Mission, Bomaderry after my adoption.

“So there was the fear of being myself. I never intended to become an Aboriginal artist, it just happened by default.”

Sally has lived in Ipswich on one side of the Bremer or another, for almost 40 years now.

Her river is long and winding but she is also deep and powerful.

With each passing year the ebbs and flows of her life become a little bit smoother.

Sally’s current exhibition EastWest refers to Sally being a child of two cultures, with a foot in both camps.

It is on at ARTtime Gallery, 203 Brisbane Street at the top of town until Saturday, 10 August.